A few years ago, I came across a short video by John Hattie discussing why inquiry-based learning showed a relatively low effect size in his research. As someone who is both an advocate of inquiry-based learning and a believer in the findings from the Visible Learning meta-analysis, this struck a chord. This question lingered with me: how could that be true when so many of the strategies with high effect sizes (e.g., questioning, discussion, metacognition) are essential to inquiry-based learning? In my own experience, I’ve seen the positive impact inquiry can have on learners, how it supports conceptual understanding, and helps students make meaningful connections. At the same time, my work as an IBEN member has given me insight into the broad range of how inquiry is understood and implemented. In some cases, I observed strong, well-scaffolded practice; in others, I saw how a lack of clarity or structure can lead to missed opportunities for deeper learning.

Inquiry-based learning often triggers strong reactions; educators either passionately embrace it or dismiss it. This tension has been discussed widely in educational literature (e.g., Hattie, 2009; Kirschner, Sweller, & Clark, 2006). At the same time, many of the teaching strategies central to inquiry, such as questioning, classroom discussion, and metacognitive reflection, are strongly supported by research and consistently linked to improved student outcomes.

Hattie (2009) explains that an effect size of 0.40 represents the average yearly growth a student typically makes. Strategies exceeding this threshold are considered to have above-average impact. Many inquiry-aligned strategies consistently surpass this benchmark. In fact, according to Hattie’s most recent synthesis, inquiry-based learning itself now has an effect size of 0.46—slightly above the average growth threshold and notably higher than earlier reported values of around 0.31–0.35 (Hattie, 2009).

You can explore the latest rankings here: Visible Learning MetaX

Why, then, does inquiry-based learning suffer from such mixed perceptions?

Common Concerns About Inquiry

First, let’s acknowledge some valid concerns. When poorly executed, inquiry-based learning can feel chaotic. Some teachers express frustration because it seems to lack clarity or clear direction. Comments I’ve heard often include:

- “It’s too open-ended; students don’t know what they’re supposed to learn.”

- “Inquiry takes too much time; we have standards and curriculum to cover.”

- “It suits advanced students, but what about struggling learners?”

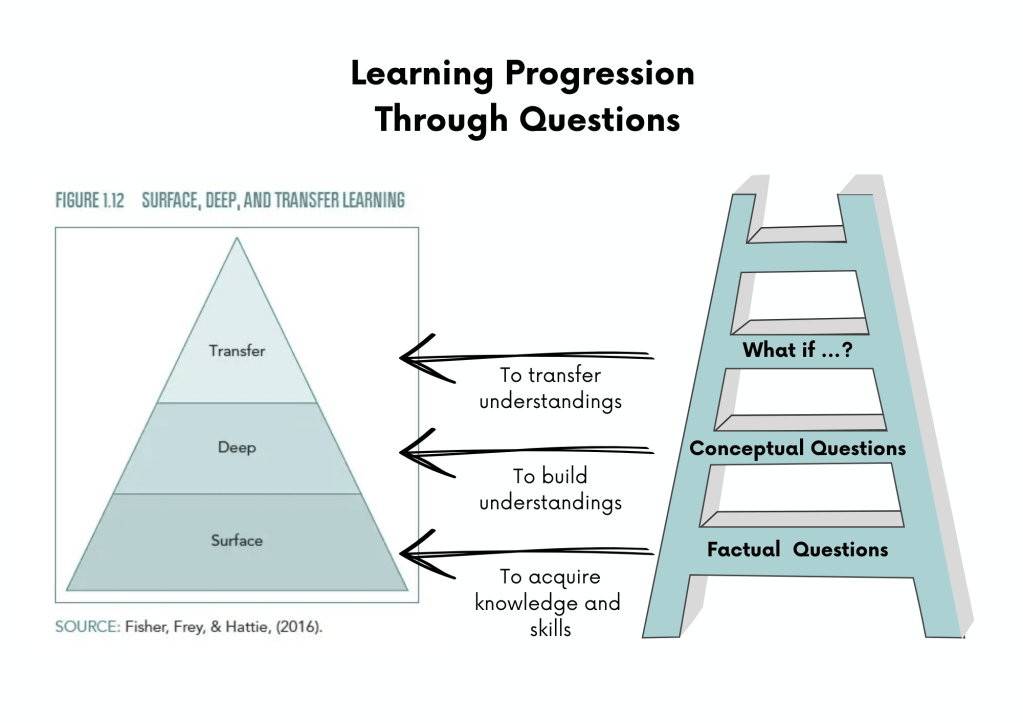

These concerns are justified. Without clear goals and effective scaffolding, inquiry can quickly lose its purpose, making it difficult for students to move from surface level learning to deeper and transferable learning.

Yet, Evidence Supports Inquiry Strategies

Strategies essential to inquiry-based learning are repeatedly validated by educational research. John Hattie’s meta-analyses, highlighted in his influential work Visible Learning, underline the effectiveness of these strategies:

- Cognitive Task Analysis (Effect Size 1.29): Breaking down complex tasks into smaller, manageable steps, teaching students the thinking processes involved, and helping them develop strategies for problem-solving and knowledge application.

- Integrating with Prior Knowledge (Effect Size 0.93): Activating what students already know supports deeper connections during inquiry.

- Scaffolding (Effect Size 0.82): Well-designed supports help learners bridge the gap between current understanding and new learning.

- Classroom Discussion (Effect Size 0.82): Collaborative dialogue encourages idea-sharing and critical thinking.

- Teacher Clarity (Effect Size 0.75): Clear expectations help learners stay focused.

- Evaluation and Reflection (Effect Size 0.75): Inquiry depends on opportunities to reflect and assess learning and make meaning from the process.

- Feedback (Effect Size 0.70): Inquiry naturally incorporates ongoing, targeted feedback, essential for student growth.

- Problem-Solving Teaching (Effect Size 0.68): A natural component of inquiry, this strategy supports application and transfer.

- Concept Mapping (Effect Size 0.64): Visualizing connections between ideas helps learners organize and extend their thinking.

- Metacognitive Strategies (Effect Size 0.60): Inquiry emphasizes thinking about one’s thinking; reflection, and self-awareness.

- Questioning (Effect Size 0.48): Core to inquiry, effective questioning scaffolds and drives students deeper into understanding and application.

Hattie’s research does indicate a lower average effect size for purely inquiry-based learning (around 0.40). However, when skilfully integrated with structured teaching approaches, inquiry methods significantly enhance deeper learning and transfer.

Common Pitfalls in Inquiry Implementation

John Hattie supports inquiry-based learning when it is structured, guided, and appropriately timed, emphasizing its value for deeper understanding and learning transfer, provided students have solid foundational knowledge beforehand (Hattie & Zierer, 2017). However, he believes inquiry appears to have a low effect size primarily due to its frequent poor implementation, such as initiating it prematurely without adequate guidance or clear learning intentions, resulting in superficial learning rather than deep, meaningful engagement (Hattie, 2009).

If inquiry strategies are so effective, why does the research suggest that inquiry-based learning has a relatively low effect size?

Typically, it’s due to pitfalls that occur in classroom implementation:

- Unclear learning intentions: If the teacher isn’t explicitly clear on the conceptual understandings, students can easily feel lost, reducing inquiry to superficial, unfocused exploration.

- Excessive student-led tangents: Inquiry doesn’t mean following every spontaneous interest. Without thoughtful guidance, students may explore endlessly without deepening their understanding.

- Weak scaffolding: Students need carefully designed supports; questions, resources, graphic organizers, and visible thinking routines, to help them transition from surface learning to deep, conceptual understanding.

- Lack of reflection and synthesis: Inquiry should always conclude with reflection and synthesis; students should continuously articulate what they’ve learned, make connections between ideas, and consider how their understanding has evolved through the process.

Getting Inquiry Right

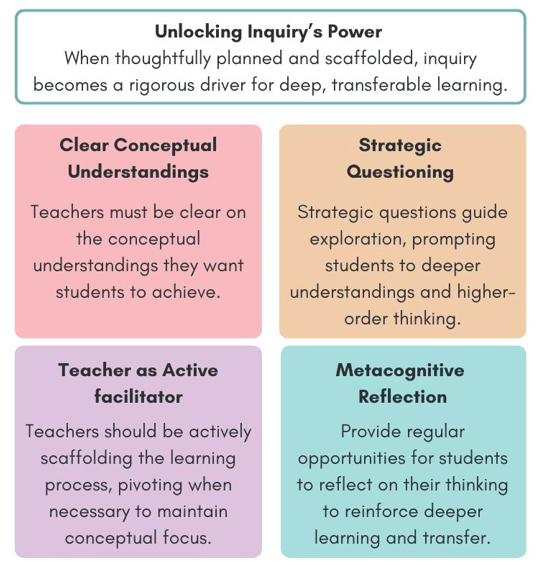

Inquiry-based learning, when done right, is structured and rigorous. Here’s what I’ve found crucial to successful inquiry, drawn from my observations, work with teachers, readings from inquiry gurus, and my own teaching practice:

- Conceptual understandings: Teachers must be clear on the conceptual understandings they want students to achieve and scaffold them using guiding questions, exploration of individual concepts, and the relationships between those concepts.

- Strategic questioning: Strategic questions guide exploration, prompting students to deeper understandings and higher-order thinking.

- Teacher as active facilitator: Teachers should be actively scaffolding the learning process, ensuring all learners are supported, identifying misconceptions as they arise, and pivoting when necessary to maintain conceptual focus and depth.

- Metacognitive reflection: Provide regular opportunities for students to reflect on their thinking to reinforce deeper learning and transfer.

- Balance with explicit instruction: Effective inquiry often includes direct teaching at strategic points, ensuring students have essential foundational knowledge and skills to successfully explore complex concepts. Hattie (2009) emphasizes that direct instruction plays a crucial role in preparing learners for deeper exploration, making it an important complement to inquiry when used purposefully and at the right moment in the learning process.

Inquiry-based learning isn’t inherently chaotic or vague; it becomes problematic only when implemented superficially or without intentional structure. The strategies essential to inquiry are some of education’s most powerful. The real challenge is mastering their thoughtful, structured application.

In short, effective inquiry demands skilled teaching; when executed thoughtfully, inquiry enhances rigor. It turns passive learners into active thinkers, capable of applying their understanding and transferring learning.

Looking to go deeper with this in your school? I offer coaching and workshops for teams and curriculum leaders. [Learn more here.]

References

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Routledge.

- Hattie, J., & Zierer, K. (2017). 10 Mindframes for Visible Learning: Teaching for Success. Routledge.

- Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86.

Leave a Reply